Cold War, Replayed—or Something New?

The question of whether the rivalry between the United States and China mirrors the Cold War contest between the U.S. and the Soviet Union is tempting because it offers a familiar frame. It suggests rules we already know, outcomes we think we understand, and a historical script that can be replayed. But familiarity can mislead. The U.S.–China rivalry looks similar on the surface, yet it operates on a fundamentally different technological, economic, and systemic foundation.

The U.S.–USSR rivalry was defined by separation. Two largely disconnected economic systems competed through military power, ideological export, and proxy wars. Technology mattered, but mostly as a tool of deterrence: nuclear weapons, missiles, space programs. Innovation was strategic, but slow-moving, state-driven, and often siloed. The Iron Curtain was not just a metaphor; it was an economic and informational reality.

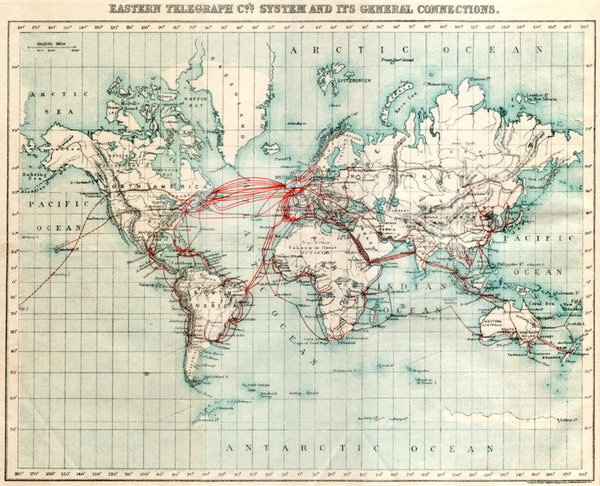

The U.S.–China rivalry is unfolding in a world of deep integration. China is not outside the global system—it is embedded in it. Supply chains, financial markets, research collaborations, and consumer technologies bind the two economies together. This creates a paradox: competition without full decoupling. Pressure without clean separation. The rivalry is less about opposing systems and more about control over the infrastructure of globalization itself.

Technology is the clearest point of divergence from the Cold War model. In the 20th century, military superiority followed industrial capacity. Today, power increasingly flows through semiconductors, AI models, data centers, rare earth processing, and software platforms. These are not purely military assets, nor are they easily nationalized. They are built by private firms, rely on global talent, and evolve at a pace that governments struggle to match.

This changes the nature of containment. The U.S. could isolate the Soviet Union because it was technologically behind and economically separate. China, by contrast, is near the frontier in multiple domains and deeply enmeshed in global production. Export controls on advanced chips or AI accelerators do not resemble the Marshall Plan versus Comecon. They are precision instruments, designed to slow specific capabilities rather than defeat a system outright. Whether such tools can succeed without fragmenting the global tech ecosystem remains an open question.

Ideology also plays a different role. The Cold War was framed as a universal ideological struggle—capitalism versus communism—each claiming historical inevitability. The U.S.–China rivalry is less about conversion and more about coexistence under tension. China does not aggressively export a global ideological blueprint in the way the USSR did. Instead, it offers a model of techno-authoritarian governance that some states may find attractive, not because of ideology, but because of efficiency, control, and infrastructure delivery.

Military dynamics, too, resist simple comparison. Nuclear deterrence still exists, but it is no longer the central organizing principle. Cyber operations, space assets, autonomous systems, and information warfare blur the line between peace and conflict. Escalation is harder to define and easier to miscalculate. In this sense, the rivalry may be more unstable than the Cold War, not less—precisely because it lacks clear red lines.

So is this rivalry on the same level? In terms of potential impact, arguably yes. It will shape trade, technology, security, and governance for decades. But in structure and logic, it is something else entirely. The Cold War was a contest between two sealed worlds. The U.S.–China rivalry is a struggle over a shared one.

That distinction matters. It suggests that analogies to the past can inform, but not predict. The danger is not that history will repeat itself, but that policymakers will act as if it must.