Electricity wasn’t just a discovery. It was a new surface the human mind could write on.

For most of history, information traveled at the speed of bodies and objects. A message moved only if a person carried it, if a ship sailed, if a horse ran, if a paper existed somewhere. Distance was not just geography—it was delay. Space itself acted like friction on human coordination.

Then electricity became controllable.

The breakthrough wasn’t merely that people “understood” electricity, or that lightning had something to do with nature. The real turning point was practical: continuous current. Once humans could produce a steady flow of electricity on demand, a new kind of communication became possible—communication that didn’t require physical movement.

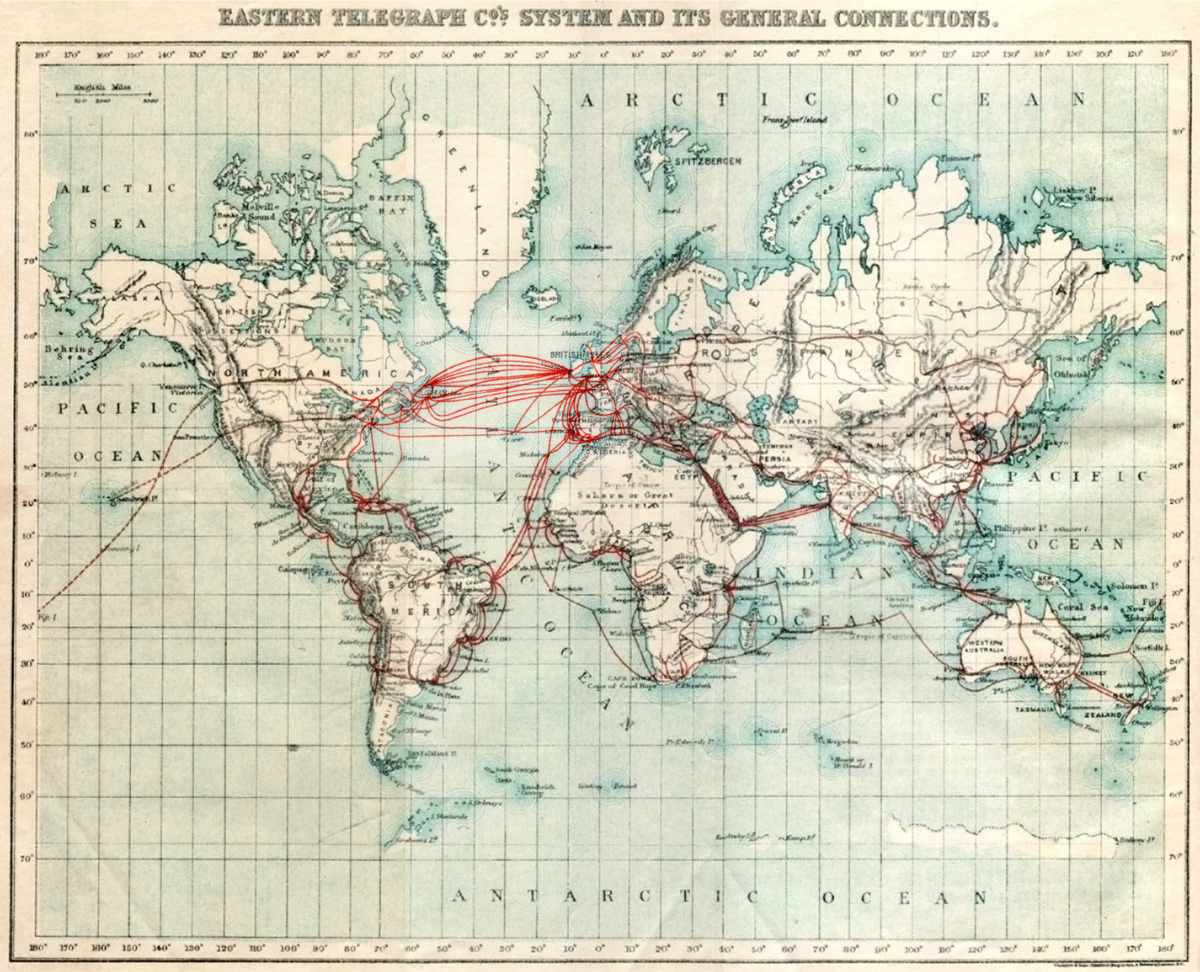

The telegraph is often taught as the invention that changed everything. But the deeper truth is that the telegraph was not the medium. Electricity was. The telegraph was simply the first widely adopted way of encoding meaning into electric pulses—an early protocol riding on a newly discovered substrate.

That distinction matters, because it reframes what technological revolutions really are.

The true revolutions aren’t always the devices we celebrate. They are the moments when humanity discovers a new underlying medium that can carry thought. Writing did this with symbols. Printing did this with replication. Electricity did this with transmission. Each time, the world didn’t just get faster or more efficient—it got a new architecture for collective intelligence.

And notice how quickly it happened: once continuous electricity was available, it took only a few decades for humans to build systems that turned it into global signaling. That’s the pattern. When a new substrate becomes stable and controllable, innovation shifts from “can we do this at all?” to “how many things can we encode onto it?” The explosion isn’t magic—it’s inevitability.

After the telegraph came the telephone, radio, television, computing, and eventually the internet. Different forms, same underlying strategy: take meaning, translate it into signals, send it across a medium. What changes is the bandwidth, the fidelity, the accessibility, and the scale—but the principle is consistent.

Seen this way, technology becomes less about gadgets and more about piggybacking. Civilization advances by finding deeper layers of reality it can ride.

So the question isn’t only “what’s the next telegraph?” The better question is: what’s the next electricity? What new substrate will carry the next phase of human coordination—one so fundamental that everything else will feel like an application built on top?

When we talk about the future, we often talk about products. But the future is usually shaped by mediums: the hidden layers that quietly change what communication, trust, and collective action can even be.

The telegraph didn’t just send messages faster.

It taught humanity a new idea:

thought can travel without bodies.

And once that idea exists, history doesn’t go back.